Ştefan Tănase

*Part of an Interview Series Taken by Sabin Borş in 2018

Ştefan Tănase is an emerging Romanian artist whose practice tackles different areas of interest, extracting particularities from different domains that are then put together, decomposed and recomposed. He describes himself as a nomad in reality and virtual reality, taking interest in new ‘worlds’ and new ‘spaces’ for living.

Sabin Borş: What motivated you to start working with digital content and media?

Ştefan Tănase: In general, you need money to do things—I didn’t have money and I still don’t have :))))) Working with digital content… Hmm… I can make a slogan: ‘Less money, more fun!’. I realised, maybe six-seven years ago, that this is one of the cheapest ways (+ some cracks) to say something is on the Internet—and now 50% of my work is based on it. Until I was 18-years-old, I shared a computer with my brother. It was difficult to do something for real, but this made me more excited to be part of the digital world and, at the age of 18, I got a scholarship and I bought my first laptop… Pretty late for this fast-forward environment 🙁

SB: You mentioned around 50% of your work is based on the Internet—what about the rest? Where do you take inspiration from and how do you transform these ideas as part of the different works you make?

ŞT: Actually, let’s say most of my work is based on the internet, but I like to have an open source every time. My current job is to deliver pizza, all day long on the scooter, see different faces, people that are happy because the pizza is delivered on time and they give me a lot of tips:))) people that are angry because I am late or people who don’t care about me, they don’t even look at me!!! They just want the pizza. This is an example of a source of inspiration that I can work on it and why not to go deeper in different ways.

SB: Is the Internet or other digital content a source of inspiration for your projects?

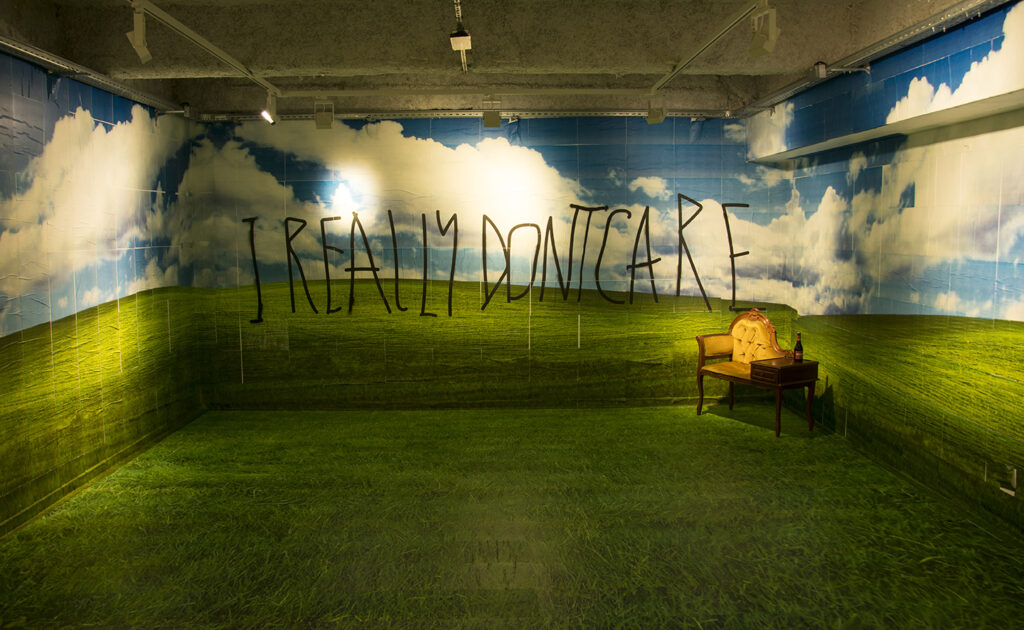

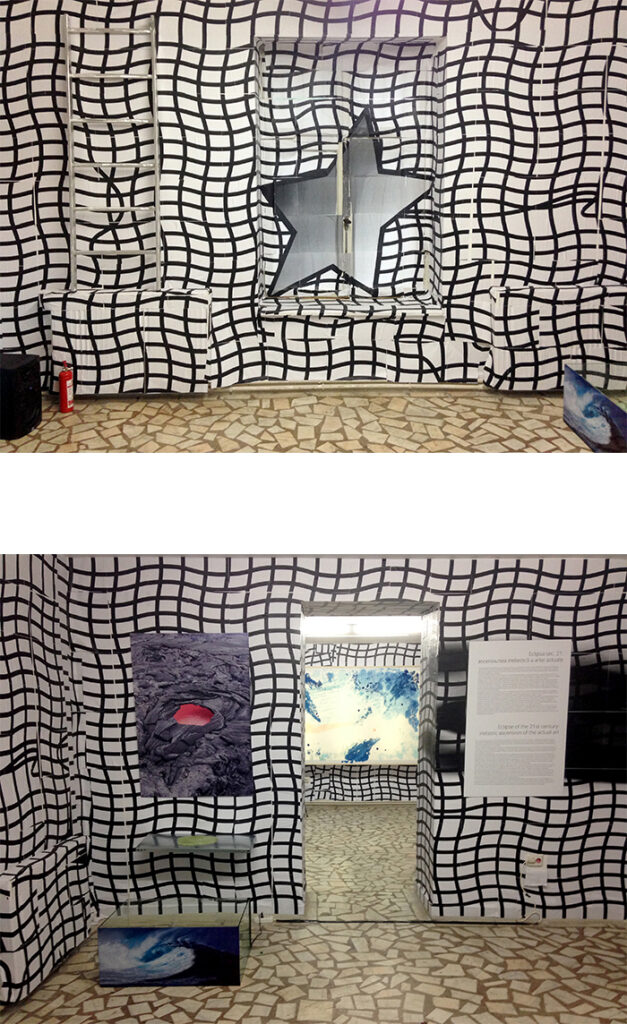

ŞT: On stage, an artist transforms even defects into qualities and vice-versa. I’m playing a ‘viceversa game’, extracting from outside the Internet into a digital form and vice-versa. For example, in 2017 I created this ‘VR’ space in a real gallery together with He Yuhui, an emerging artist from China. For this piece, we glued 1,200 A3 sheets on a white cube. The idea was to create confusion and distortion between realities. Where is the border? Is it a border? We are used to seeing daily things (buildings, cars, trees, etc.) but not the places that lie between these two worlds. We then did a VR video with the room that describes a certain endlessness— everyone can fill up the ‘naked room’ again and again and again… After this project, I was invited to Bucharest to do the same thing for a group show, but on a larger scale this time.

SB: Is digital media more appealing for you than other media?

ŞT: Like I said before, I guess it’s one of the cheapest ways to express yourself, plus the information can touch a large public much faster. There is enthusiasm in knowing that someone from another part of the world can see my work and we can discuss about it. For me, it’s a social democratic place where we can grow up together—a new world. This interview too, is the result of the digital environment.

SB: Are there any specific influences in the way you developed your projects, something that you appropriated deliberately in your work as a result of this?

ŞT: It’s an anecdote, a math equation that cannot be resolved yet :))) I played football for half of my life, until now—I don’t know how I arrived here. I remember that the football environment in Romania was without perspective and, at the age of 12, I didn’t want to play anymore. In the past 2 years, I extracted ideas that go from the field of DNA to sci-fi and, recently, to robots. When I finished high-school, art had become boring and I wanted to change something in my life. I was interested in science and technology; as an ‘artist’ in high- school, in the 10th grade, I stopped all science lessons because I was going to a school with an artistic profile… Anyway, I’ve been scared by all the science classes up to the 10th grade :)))) After high-school, I understood that I lack basic knowledge of science. I started to read and now the thought of knowing about science excites me. Maybe in that period, I realised the future of art is, in a way, related to science and technology 😛 😛

SB: Did this make you create any particular elements in your work whereby one could identify your work? Do you think your artistic practice belongs to any specific category?

ŞT: As you can see, each one of my projects is pretty different aesthetically. I have lived in different contexts, with many different people, from my neighborhood in Bucharest to the East of France, Besançon, and now in Lausanne; with football players, people who did prison, artists, douchebags, geeks, rich people, junkies, poor people, homeless people, site workers, etc. I extracted a bit from everywhere—all those things make me pay more attention and be more aware of what is around me. Because I have this background, I think my work is divided into categories and these categories are linked with four big lines: inter-human relationships, nature, science and technology, graphics and design.

When it comes to my practice, I usually start with an idea, then I analyse and make the connections until a nucleus/concept is formed; afterwards, I try to find the right environment to communicate—it’s not the same every time anyway, it depends on the purpose. I didn’t put my art on a pedestal yet, but it could be described as ‘post-internet art’.

SB: Given the many different expressions and techniques encompassed in your works so far, how easy is it for you to negotiate between the digital and the physical, especially when it comes to displaying or exhibiting your work?

ŞT: I like to find an in-between way every time—an intermediary between the screen and the physical space. when you enter the physical space, it could be something else, something that makes you lose contact with time and space for a few seconds. When it comes to the screen, I like it when I do something and you don’t know if it’s real or not. This could be one of my goals, to invent a world where you never know whether it’s real or not—and I don’t mean VR. I think it’s complicated when you want to make a group show and it also depends on the context… I mean, space doesn’t matter, it could be anywhere really—what is more important is to know what you want [to do] and how can you adapt your idea in any given space, ideally with a minimum or basic budget. In general, if I like the project and I relate to it, I’m in. I didn’t have that many opportunities to refuse an exhibition :))))) But if I would receive an invitation for a show that doesn’t match my ideas, I think I’d say no. Again! it depends on the context, it can be something that you don’t like in the beginning, but in the end it proves to be crazy. It’s back and forth.

SB: Is there any of your works that you think is more representative of your overall approach?

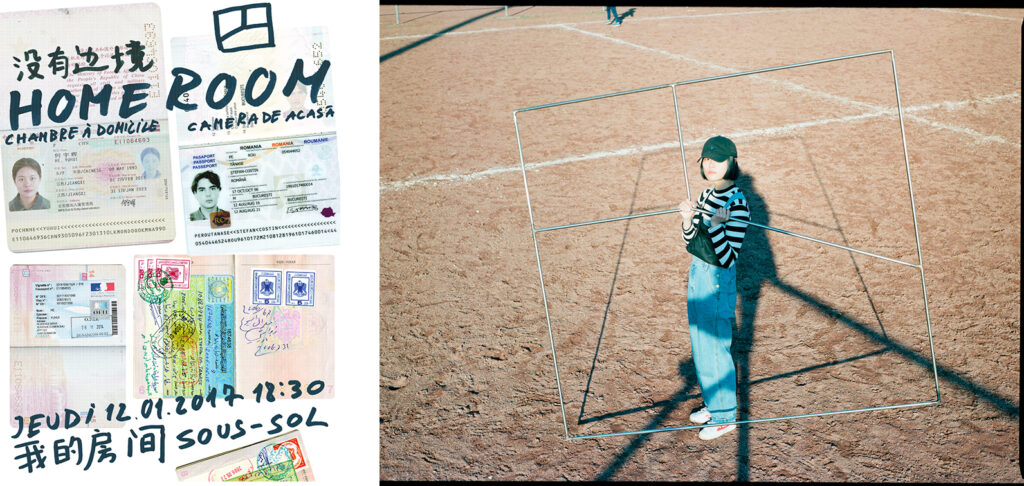

ŞT: Until now, Home Room and The first night after the wedding and “Trust makes it simple” my last project. These are two consecutive projects that relate to each other and define my vision and my work so far, I think. Also, the last project comes as my ‘genetic transformation’ since I arrived in Switzerland, many things have changed radically and I told myself that I have to become a ‘genetic designer’ + some previous ideas about Chinese social ranking and in general statistics and rankings.

SB: You kept the idea of using the sheets for the group show installation you mentioned at the beginning of this interview—Eclipse of the 21st century / The inelastic ascension of the actual art. Could you please tell us more about this project? What does the title refer to and how did you see your work in relation to the other works in the show?

ŞT: Yeah, I think my work comes as a generated pattern who links the curator’s idea with the works of others, ‘an intermediary between the worlds’, dotting the I’s. “The actual becomes functional through codes generating and encryption methods, cryptography being the field of perception and definition of every existential moment. Implanting a visual code reflects into a game of the multiplicity of alternative realities, these being the main axis of the concept that sub-divides into four perspectives: reassimilation, real-virtual, fastforward, synesthesia. All these absorbing and dissolving environments form a series of alternative realities that develops under the patronage of the fueling engine of dissolutions and fusions, becoming directly proportional to the limitations imposed by this era of the anthropogen and implicitly of its orbiting uncertainty. The curatorial experiment proposed to the artists focuses on the point where game rules get indicative nuances in this dimension of alternation, but where an image will remain an instrument or a model even if an unpredictable pattern.“ Curator: Adrian Bîndiu

SB: In one of your most recent projects, The Perfect Citizen, you approach the Chinese social credit system. How did you become interested in this idea? Did you also intend the project asa social critique or looked to discuss the topic more closely related to the social problems it involves?

ŞT: With The Perfect Citizen, I started from the social credit system in China. Through an app (WeChat), everyone has a score of who is basically controlling and dictating your life. For example, you are punished if you don’t pay your taxes on time or if you order things from Japan. The project comes as a visual hacking tool for the Chinese social credit system. I think we can exclude this part because it’s part of “Trust makes it simple”, but at that moment I didn’t have the project finished.

SB: How important is software and hardware in developing your work?

ŞT: Hmm, I’ll start with a funny and sad story :)))) Two years ago, when I moved to France, I wanted to print something from a school computer that was running in French. I didn’t understand very well and I pressed a button called ‘effacer’—I erased 500 GB of my work and memories from the hard drive. Long story short, I did a backup from the computer to my hard drive but finally recovered just 5% of what I had. It’s pretty hard to keep the data safe, so now I use drives and the cloud, but I’m still scared of losing everything again. I’m using everyday software for my work and I need a good processor, data storage, graphic card, etc. to make it possible. I haven’t used code yet, but I made a proposal this year. I learned the software in general by spending hours and hours in front of my PC.

SB: Was there any interest in ‘digital art’ and ‘digital media’ back in the art school in Romania?

ŞT: I don’t know exactly, but in my case—or the case of my generation—not that much. On a scale from 1 to 10, I think it’s at around 3. As we can see, everything adapts daily and digital art should be basic in an art school, simply because it can open many roads and can be more fascinating. It is not bad to sculpt, paint, or draw, but it is better to have more choices. Most of the people from my generation have stopped doing something related to art after highschool. I guess that’s because of lack of enthusiasm or reasons to go on. I don’t say everyone needs to become an artist after high-school, but they can work in the creative industry. In the 11th grade, I went with a school exchange to a high-school from North-Eastern Italy. It was the complete opposite of my school—they were working only digitally and they had all the necessary equipment for just about anything in school. From the 11th grade, they were already working with companies and magazines through the school—making websites, layouts, posters, etc. It’s just an example, but the principle idea is to form a base culture.

SB: Do you think it is easier to find support with art galleries or institutions?

ŞT: I don’t know exactly, you can find people every time who can relate to you and support whatever you do. Four years ago, I got a scholarship from a foundation—I was young (I still am :))) ) and it was nice, looking from a financial perspective, but they weren’t so open to everything.

SB: How has digital visual culture changed over the past few years, in your opinion, and how does it impact the local scene? Do you see any particular changes in the way people relate to digital media and the Internet?

ŞT: [It changed] just by the simple fact that we have Instagram and it’s easier for everyone to see almost everything super fast, without even wanting any of this. Everything is connected and everyone is equal, everything is now! It’s clear that we are influenced by that, and not just on the local scene particularly. The only thing I noticed is that young art students are more ‘now’ than my generation. It’s a lot of information that you can choose from to go deeper. More than ever, I think half of the world has access to the Internet and, in my opinion, this is just the beginning. Most of the users are from Asia, North America, and Europe, but I think about the day when everyone will be connected to each other. We start accepting robots, AI, and virtual models in our daily life—it’s a new outset 😀 😛

Ştefan Tănase (b.1996) is a multidisciplinary artist interested in what he calls ‘’sugar, spice and everything nice’’- topics ranging from the off-world, to magic, experiments, rituals, networking, delivery, science, and what it’s like to live in the 21st century as a millennial migrant. With a background in graphics (National University of Arts Bucharest from 2015-2016) and visual communication (Higher Institute of Fine Arts, Besançon, France from 2016-2017), Ștefan Tănase is currently studying fine arts at the Cantonal school of art and Design of Lausanne (Ecal), in Switzerland, where he’s looking to decompose, scan and deliver power, happiness and crazy energy.

Sabin Borș (b. 1981) is an independent editor and curator who also works as freelance layout designer for various web and print cultural projects. He is the founder and editor of the anti-utopias.com contemporary art platform and has been working for various specialised print and online media outlets in the field of art and architecture since 2009. In parallel with his Ph.D. thesis in philosophy—tackling the subject of archives, discourse, and contemporaneity—he started developing a multi-modal archival installation. The installation is intended as a critical approach to constructing cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary frameworks for the documentation, interpretation, and dissemination of contemporary art, providing alternative understandings of the socio-political foundations of art, constituent cultural differences and transitions, or superposed cultural, scientific, and technological interactions. He takes particular interest in dialogical constructions that create divergent networks of meaning between mediums, disciplines, and practices.