Tristan

*Part of an Interview Series Taken by Sabin Borş in 2018

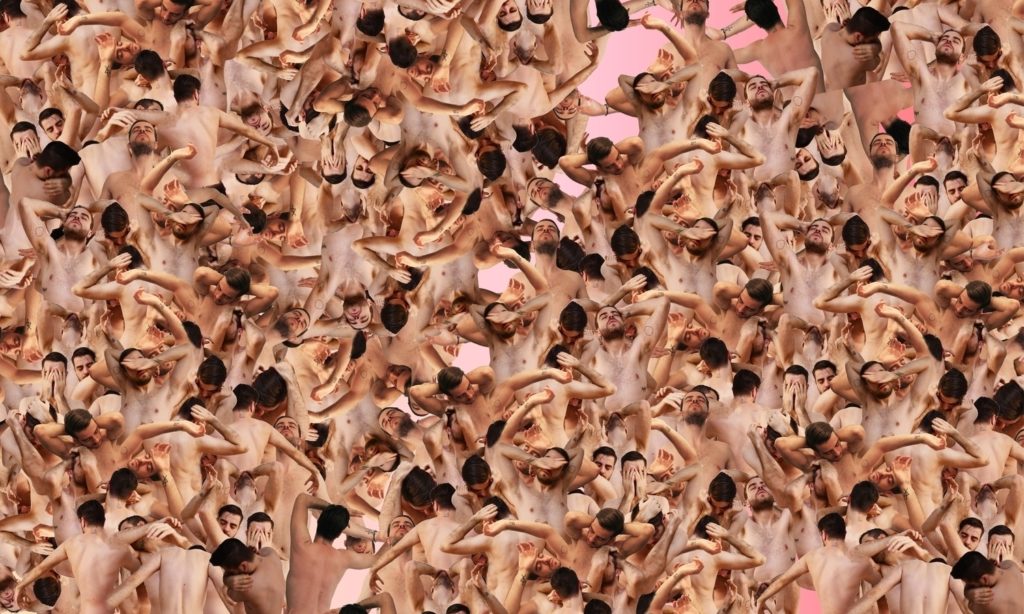

Tristan is a visual artist whose artistic practice is based upon the relationship between online identity and the effects it has on the mental imagery of oneself. His work is concerned with the intersection between online space and real life, focusing on the impact of Internet culture on identity. His interest in the digital performance of the self has been constant and manifested through mashups of pop items, patterns of religiosity and sentimentality, 3D creations and the obstinate build-up of an online persona which surpasses his live presence.

Sabin Borş: Your work relates closely to issues of identity and online presence—how did the Internet become a subject of interest for you?

Tristan: I started working with digital content around 2009-2010 and, also around that time, I really started to take it as a serious alternative way of expressing what I wanted to but wasn’t able to express with my traditional fine arts background. In the beginning, my work didn’t relate that much with the Internet, but as time passed by and my social media accounts grew, my online presence and interactions also multiplied—therefore, my work also started to be more and more connected with the Internet. I’m very fascinated about identity and how the Internet and social media have a powerful effect on it. Even if some of my works seem to be from outside the Internet, they are deeply connected with what happens online.

SB: Why does the issue of ‘identity’ take centre-stage in your work? How does it relate to the idea of corporality as a physical and immaterial matter?

T: It takes centre stage in my art because identity can be such a complex sum that forms the DNA of who we are in the real world. But the Internet can be an essential mark of the process of identity construction. So, in my works, I also play with the different ways in which identity and alter-egos can be curated on social media platforms via the Internet and how these processes can be symbols of renewal too. The aspect of corporality in my work has to do more with my sexual identity and how the body—and, in this case, the male body—is an important aspect in gay culture, so much that it becomes objectified and fetishized.

SB: You mentioned you were not able to express certain ideas with your traditional fine arts background. What did you see differently in working with digital media?

T: I like to work with digital content—and I find it more exciting than the traditional ones—because of the endless remixing possibilities that it offers. In a way, it’s the ultimate post-modern way of expressing my ideas. I’m shaped by the digital realm and, in return, I like to think I too can shape it.

SB: Were there any particular influences—in terms of ideas or other artists—that shaped your personal perspective?

T: My influences are mostly audio and come in the form of music. But there are also a few digital artists who count as influences, mostly from an aesthetic viewpoint—to name just a few: Jon Rafman, Cécile B. Evans, Jesse Kanda, Andrew Thomas Huang, Arca, or Sam Rolfes

SB: As such, would you say your artistic practice could be described by the dominant and trendy denominations used to describe digital art creations?

T: I don’t really like to be labeled as a ‘post-Internet artist’ even though I make use of ‘post-Internet’ concepts in my work from time to time. Recently, I’ve become more interested in time-based media and video art. My artistic practice is very self-referential, so much of what I create has to do with my own bodycorporality and identity, as well as the ways in which they can transcend into the digital realm.

SB: This means there is always a relation at work between your personal experiences, virtual mediation, and the physical again. Does this also translate into the way in which you conceive your exhibition displays?

T: Most of the time, in the process of translating my work from screen to the real space, I encounter lots of problems. That is why, most of the time, my recent works (at least) are meant to be seen and displayed on a screen or as a projection. When I think of certain projects that are meant to be part of an installation, I conceive it most of the times without the space limitations involved; but one of the things I love about digital works of art and the entire process of it, is the idea of no galleries. I see all the different platforms on the Internet as a more authentic way of displaying what I created than a white cube type of space.

SB: Why is that, more exactly? In what way does the physical affect the ‘authenticity’ of your digital work?

T: Mostly, because I think the physical aspect affects the authenticity of my work during the process of transforming the digital and immaterial into something physical/material. It becomes something different than the initial intention and can lose lots of qualities that only the digital medium can offer.

SB: Are there any particular works in your portfolio that would be more ‘representative’ of your ideas and approach?

T: Probably my recent series of digital self-portraits.

SB: Is there any reason for this? How does this series differ from your previous works?

T: This series differs from the previous works I’ve done simply because I consider them to be more consistent. I feel I’m more mature and have gained more experience and confidence in what I want to express through my art.

SB: Is the software and hardware part relevant in conceiving your artworks?

T: Most of the times, software training and learning about certain programs and apps is more important than the hardware part in my artistic practice. Everything I know is self-taught out of need and curiosity.

SB: You already mentioned that traditional art practices continue to be the backbone of artistic education—do galleries and other institutions provide any alternatives in this context?

T: I would say that the major art galleries and institutions in Romania—or at least in Bucharest—still prefer to invest and take into consideration very conventional works of art. These can be more easily turned into profit, if we talk about commercial galleries. Most of the institutions don’t understand art in general, so they definitely don’t understand the specificities of working with digital content. Certain peripheral projects and alternative spaces do take into consideration digital content and work with digital artists, but this is something relatively recent and not completely established.

The only gallery that I worked with and was represented by, for instance, simply considered my work as being ‘cool’ and ‘trendy.’ I was very superficially categorised into their ‘digital artists’ portfolio, only as a way of enhancing the ‘non-conformist’ reputation of the gallery. Right now, I am not represented by any gallery—and therefore, don’t get by as an artist.

SB: How does this situation reflect the local context?

T: The fact that I’m one of the handfuls of people working with digital media and content—and working with such content ever since 2010—in Romania, I think is an important historical aspect in the local and regional art scene. There are a few art collectives that only work with digital content in Romania, but most of the digital art is produced in Bucharest and Cluj. I would even say that Cluj is a more fertile ground for this type of art to grow and get more recognition in the art scene.

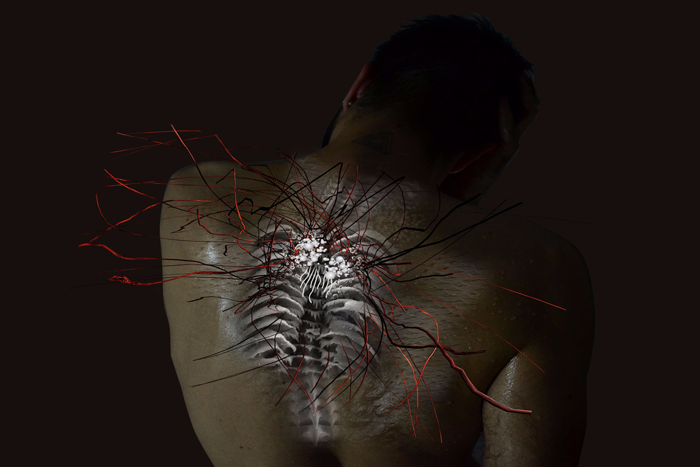

Digital Wounds, Tristan

SB:Why is that? After all, Cluj is mainly known for its ‘myth’ concerning the new wave of figurative painters after mid-2000s… Why do you think it could be a more fertile ground?

T: That’s true, when talking about the ‘myth’ with the new wave of painters. But I think there are a few young kids excited and curious to experiment with digital art, who try to detach themselves from this overhyped ‘myth.’

SB: How did digital visual culture—and the Internet—change over the past few years, in your opinion? Did it affect the local scene in any way?

T: Digital visual culture might only affect the local scene in a very minor way. The fact of the matter is that digital content produced in Romania and Romanian digital artists are still almost invisible on the local scene—they are not fully validated and acknowledged.

One of the biggest changes in our relationship with the Internet is the fact that we are connected all the time to it nowadays via smartphones and Wi-Fi access everywhere. So we perceive and interact with the Internet in a much deeper way than before. This accessibility of the digital realm that the Internet offers you, makes the digitally produced content more reachable and direct than 10 years ago, more or less.

SB: We may have this feeling because there has been so much content produced and put out on the Internet in this past decade, that it has become virtually impossible to keep track of very specific changes, let alone the wider or more structural changes. Do you think this information and data overload—which certainly impacts our online presence and identity—will lead to a systemic block or redundancy that will see people slowly trying to disconnect from the Internet?

T: To be honest, I don’t think that data overload and the redundancies brought by this phenomenon will make a great impact, or that people in large numbers will try to disconnect from the Internet. I think the trend is a complete symbiosis between man and technology, thus creating a new type of human in the near future.

Tristan (b. 1989) is a Romanian artist who lives and works in Berlin, Germany. He studied graphic arts at the University of Fine Arts in Bucharest. His most recent exhibitions include Stimulation Overload, Superchief Gallery SOHO, NYC; Future of Art part 2, NewHive; Goethe- Institut, San Francisco; and Is it wrong that I enjoy cutting people in Photoshop?, Suprainfinit Gallery, Bucharest. He experiments and works with vector images, 3D modelling, and digital collages.

Sabin Borș (b. 1981) is an independent editor and curator who also works as freelance layout designer for various web and print cultural projects. He is the founder and editor of the anti-utopias.com contemporary art platform and has been working for various specialised print and online media outlets in the field of art and architecture since 2009. In parallel with his Ph.D. thesis in philosophy—tackling the subject of archives, discourse, and contemporaneity—he started developing a multi-modal archival installation. The installation is intended as a critical approach to constructing cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary frameworks for the documentation, interpretation, and dissemination of contemporary art, providing alternative understandings of the socio-political foundations of art, constituent cultural differences and transitions, or superposed cultural, scientific, and technological interactions. He takes particular interest in dialogical constructions that create divergent networks of meaning between mediums, disciplines, and practices.