Vlad Anghel

*Part of an Interview Series Taken by Sabin Borş in 2018

Vlad Anghel’s practice is located at the intersection between art, design, and technology. In his work, he often appropriates obsolete 3D aesthetics and surrealist references, creating virtual environments that can be described as magical realism.

Sabin Borş: How important was the Internet in the way you started working with digital media and in informing your vision?

Vlad Anghel: My practice always revolved around creating work based on and inspired by the Internet. I would go as far as to say that my work would not be able to live without it, because it was created with the Internet in mind. My work is consumed fast, it is easily accessible and re-mixable, and it’s a perfect fit for social media platforms. I started working on the Internet six years ago, but I started showing it in art institutions only three or four years ago. It all began as a way of expressing myself. For me, the Internet was a safe space where I could have a voice and where this voice could be heard. It was an outlet for venting out my frustrations. On the other hand, because I am working mainly in 3D, I find it very interesting to translate things from outside the Internet and see how they would behave on it. You get some pretty uncanny results sometimes. Working with digital and especially with 3D is like walking into uncharted territory, and that is exciting for me. Also, it was much easier to express myself on the Internet and connect with people who had the same interests as I did. I started out by using Tumblr as a platform for showing off my art—and I would also use and remix Tumblr content to create my own works as a result. I would use anything I could find online, from textures to paintings or free models, putting them together in a new and more interesting way. Everything online was an influence for me.

SB: You did not study art but cybernetics, statistics, and economic informatics—so how did the transition towards art take place? What did you find fascinating about art and digital art in particular?

VA: I studied programming in university but we didn’t have any creative classes apart from an outdated web design class. I was very much into combining programming and arts—and that’s how I got into Processing, a software for generative art. The idea of code informing a unique visual artwork every time the program ran was very appealing to me. Also, my partner at that time was studying arts, so I would say he was an influence as well. The idea of ownership was really fascinating to me. I enjoyed seeing my digital works remixed or republished—loosing control over them. For example, a dental office in Mexico downloaded one of my works and used it to promote their business; I didn’t mind it, on the contrary, I found it quite fascinating.

SB: For someone without an artistic background, you have a very keen sense of aesthetics—was this informed by anything in particular?

VA: I think practice makes it perfect. I used to read as many art and design books as I could, and I assimilated many images off the Internet. It was all natural and I really enjoyed it, so I think an interest in aesthetics also helps.

SB: The intersection between digital art, on the one hand, and cybernetics, on the other hand, is quite inviting, don’t you think? Did you ever consider working around these subjects?

VA: There are concepts in cybernetics that I take a lot of interest in, like cognition, learning, emergence, or simulation.

SB: Do you think your works fall in any specific artistic categorisation?

VA: I would like to believe that my art doesn’t fit into a particular form of art. I think it morphs and changes along with my interests. I am not interested that much in the medium as I am focused on what I want to express.

SB: But given the peculiarities of this medium, in general but in the arts especially, is it so easy to discard them and see it simply as an instrument for artistic creation? Can we so easily avoid the constitutive properties of the medium? What sets it apart from other media then?

VA: I used to describe myself as an image-maker. I like this concept because it focuses on the idea of crafting an image, just like painters were craftsmen in the beginning. My tools of choice are computers, so I guess, because of that, you could say that my art can be categorised as digital art—but even that becomes more blurry nowadays, with new forms of expression like mixing performance with holograms or augmented reality.

SB: How do you exhibit digital content in a physical exhibition space?

VA: In my short experience with exhibiting works, I found it quite challenging to translate digital art to the physical space, and yes, it happened that I didn’t want to exhibit a work because the curators were insisting on literally translating a 3D scene in a physical setting. I think you have to be careful how you exhibit digital art. I usually do prints or use TV screens to show my work, in order to stay true to the digital aspects. I really like the square format of Instagram and it’s something that I would also like to explore more for the physical space. The 3:4 ratio is also a great format that I take interest in.

SB: Do you think there is an artwork in your series that best represents your vision?

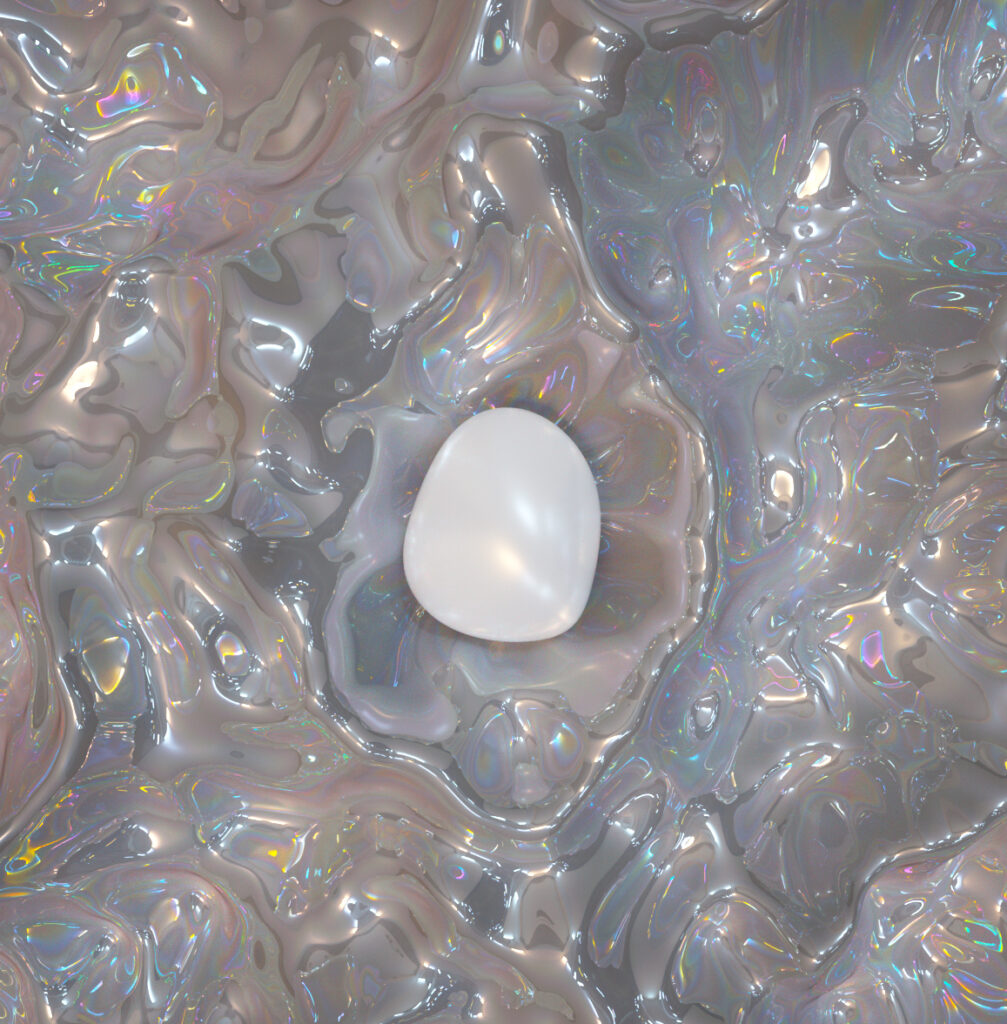

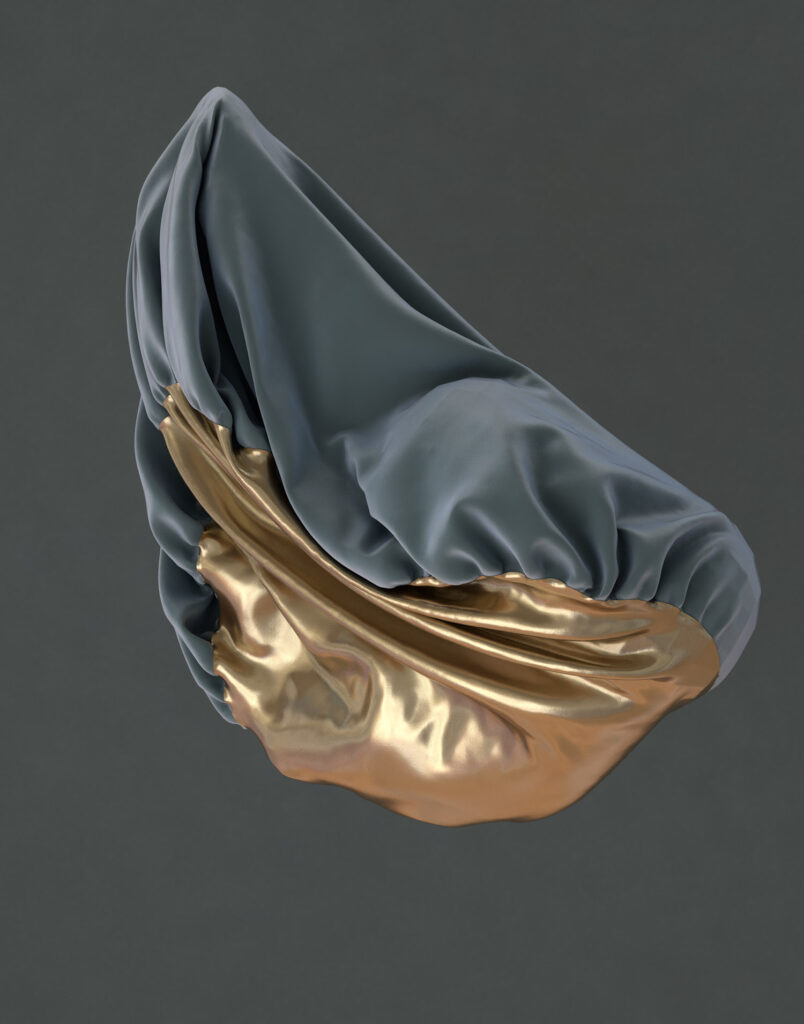

VA: I think the Shell series of works are very close to my heart. I work less with human models than I do with objects and still life—but the objects are usually anthropomorphised. The shells have an erotic human-like quality to them.

SB: Are there any formal or iconographic elements that you prefer working with?

VA: I tend to work mostly with objects found in nature, like rocks or shells. We live in a human-centric world and I would like to take the accent away from that. How would history look if it were be rewritten from an object’s point of view?

SB: Did you consider using code to develop your works?

VA: I actually started working with code initially and then moved to 3D. For me, the tools that I use are important in that they help me achieve the effect that I want and nothing more.

SB: How easy was it for you to find support for your work with art galleries and how do you get by as a digital artist?

VA: I found support with some galleries back in Romania, but I think the problem was that of the production budget. People usually want to support you, but since there is not much money for art in Romania, we would be let to find our own ways to produce the artworks. In my experience at least, I had a difficult time collaborating with the curators I worked with in Romania because they would have a difficult time translating digital art into the physical space. I think it’s very important not to remove the digital out of the artwork. I don’t get by as an artist and I never did. I have a full-time job but I would say that I am lucky enough to work in the same domain as my artistic practice.

SB: You mentioned before that people have categorised your work as ‘post-Internet art’ but that you don’t think this term represents it very well. Instead, you have described your virtual environments as ‘magical realism’. Could you please detail this idea of magical realism and the specific way in which it relates to your work?

VA: For me, it’s about simulating reality by using digital means—but observing how totally new patterns emerge from algorithms instructed with a seeming degree of freedom.

SB: Do you think there is anything particular about the way in which the Internet was appropriated in post-socialist countries?

VA: I think the Internet in post-socialist countries was a form of escapism and digital art has about the same tendencies too. I also think that this has the potential to become a catalyser for really original works. It’s a bit different from Western countries, where this is already established and people follow each other’s styles.

SB: While it’s interesting that you mention this potential for original works, it’s actually rare that such potential is achieved. The iconography and motifs referenced by many digital artists remains a rather uniform language, with very little space to accommodate difference at times. Where does this ‘originality’ lie, in your opinion, and how could it be brought to life in a more engaged way?

VA: I believe originality lies in allowing your work to be informed by your immediate experience. Many digital artists are inspired by other images, but the image itself is just a representation.

SB: Is there any change within the field of digital visual culture—and the Internet itself—that you notice taking place?

VA: We are now more than ever oversaturated by visual content and people are becoming more insensitive to it. I think this desensitisation happening on a large scale will see artists creating even more provocative art or art that disrupts the current status quo. In what concerns the Internet, I would go as far as to say that the Internet as we know it is dead. Although it is very vast, it became this very narrow and unoriginal place because everyone is using the same two or three applications on their phones most of the time. Surveillance is also a very interesting and expanding topic.

Vlad Anghel works as a multi-disciplinary artist in Berlin and Bucharest. He was the assistant curator and co-producer of D’EST Prologue: O’ Mystical East and West (2016) at Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin. He studied Cybernetics, Statistics, and Economic Informatics at the Academy of Economic Studies in Bucharest.

Sabin Borș (b. 1981) is an independent editor and curator who also works as freelance layout designer for various web and print cultural projects. He is the founder and editor of the anti-utopias.com contemporary art platform and has been working for various specialised print and online media outlets in the field of art and architecture since 2009. In parallel with his Ph.D. thesis in philosophy—tackling the subject of archives, discourse, and contemporaneity—he started developing a multi-modal archival installation. The installation is intended as a critical approach to constructing cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary frameworks for the documentation, interpretation, and dissemination of contemporary art, providing alternative understandings of the socio-political foundations of art, constituent cultural differences and transitions, or superposed cultural, scientific, and technological interactions. He takes particular interest in dialogical constructions that create divergent networks of meaning between mediums, disciplines, and practices.